Introduction

This is something of an ongoing review, chapter by chapter, of Gary Taubes’s extraordinarily dense book Good Calories, Bad Calories, which I usually shorten to GCBC. You might even consider this more of a fact-checking than a review, but whatever. I’m not going to get into a semantic argument. I wrote my first review of this book back in 2012, but after writing it I felt very unsatisfied. GCBC is such a dense book filled with so many unsubstantiated claims that I felt the book demanded a more thorough review. Other bloggers, like James Krieger at Weightology, seem to feel the same way and have tried to provide such a review only to eventually give up once they realize the gravity of the task. I may also give up at some point. I actually have given up a number of times only to feel compelled to hit at least one more chapter.

If you would like to read other parts of this ongoing review go to the table of contents on my Book Reviews page. FYI: All page numbers in this review refer to the hardback version of the book.

Not the Introduction

Early in the chapter Taubes claims that most mainstream nutrition authorities were saying that the American diet changed during the 20th century, from a plant-based diet to a diet heavy in meat. On pages 10 and 11 he attempts to refute this notion by saying that the USDA statistics from which this notion is drawn is very flawed, citing a personal interview with David Call and a paper on food disappearance data.1 Specifically he says

-

“The USDA statistics, however, were based on guesses, not reliable evidence.”

-

“The resulting numbers for per-capita consumption are acknowledged to be, at best, rough estimates.”

-

“The reports remained sporadic and limited to specific food groups until 1940 […] Until then, the data were particularly sketchy…”

However, the very next paragraph he makes the argument that the US has always been a meat-eating country, and as evidence he cites data from the USDA! “By one USDA estimate, the typical American was eating 178 pounds of meat annually in the 1830s, forty to sixty pounds more than was reportedly being eaten a century later.” Either the food stats are reliable before 1940 or the are not. Pick a side and be consistent.

He’s really all over the map in this section because he then claims that in fact we did eat less meat in the early 20th century due to a few reasons: the cattle industry could not keep up with population growth, meat rationing during WW1, and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. He then makes the argument that Americans started eating more fruits and vegetables and decreased consumption of animal products. Following this change, incidents of heart disease skyrocketed to become an epidemic – an epidemic that earlier in the chapter he claims was completely bogus.

* * *

On pages 14 and 15 Taubes talks a bit about cholesterol and says

Despite myriad attempts, researchers were unable to establish that patients with atherosclerosis had significantly more cholesterol in their bloodstream than those who didn’t. “Some works claim a significant elevation in blood cholesterol level for a majority of patients with atherosclerosis,” the medical physicist John Gofman wrote in Science in 1950, “whereas others debate this finding vigorously. Certainly a tremendous number of people who suffer from the consequences of atherosclerosis show blood cholesterols in the accepted normal range.”

It’s interesting to note that immediately after that sentence in the cited text Gofman also wrote2

There does exist a group of disease states (including diabetes mellitus, nephrotic nephritis, severe hypothyroidism, and essential familial hypercholesteremia) in which the blood cholesterol level may be appreciably elevated. Such patients do show, in general, earlier and more severe atherosclerosis than the population at large.

In fact, most of the text makes the case that there are particular cholesterol particles to blame for atherogenesis, specifically those with a density of 10-20 Svedberg units that are currently known as LDL. However, since this paper was published in 1950 they are referred to as the Sf 10-20 class of cholesterol molecules. Gofman also noted – prior to even anything that Keys published on the subject – that dietary lipids affect these Sf 10-20 molecules, stating:

Our preliminary study of a group of 20 patients whose diet we have restricted in cholesterol and fats has demonstrated that the concentration of the Sf 10-20 class of molecules is definitely reduced or even brought down to a level below resolution ultracentrifugally in 17 of the cases studied within two weeks to one month.

I can’t understand why Taubes didn’t mention that, can you?

* * *

Taubes knocks me for a loop on page 15 when he states:

The condition of having very high cholesterol—say, above 300 mg/dl—is known as hypercholesterolemia. If the cholesterol hypothesis is right, then most hypercholesterolemics should get atherosclerosis and die of heart attacks. But that doesn’t seem to be the case.

Actually that seems to be exactly the case… even by the study Taubes cites.

That study even seems to be in agreement with the other studies on familial hypercholesterolemia at the time3:

Our results are qualitatively similar to analyses on a smaller scale which have established an enhanced risk of premature CAD in affected members of families with familial hypercholesterolemia.

But since certain thyroid and kidney disorders might also cause hypercholesterolemia I suppose Taubes can just ignore all that evidence linking cholesterol to heart disease.

* * *

Pg. 15

Autopsy examinations had also failed to demonstrate that people with high cholesterol had arteries that were any more clogged than those with low cholesterol. In 1936, Warren Sperry, co-inventor of the measurement technique for cholesterol, and Kurt Landé, a pathologist with the New York City Medical Examiner, noted that the severity of atherosclerosis could be accurately evaluated only after death, and so they autopsied more than a hundred very recently deceased New Yorkers, all of whom had died violently, measuring the cholesterol in their blood. There was no reason to believe, Sperry and Landé noted, that the cholesterol levels in these individuals would have been affected by their cause of death (as might have been the case had they died of a chronic illness). And their conclusion was unambiguous: “The incidence and severity of atherosclerosis are not directly affected by the level of cholesterol in the blood serum per se.”

I was unable to find the cited Landé and Sperry paper. It is so old and obscure that not only was I unable to find it, the databases I used (PubMed, WorldCat, Academic Search Complete) could not find a record of it even existing. But let’s do something we probably should not do and take Taubes at his word here. It is still interesting to note that this is an example of an observational study, specifically a cross-sectional study. Later in the book Taubes will make the case that observational studies are worthless. In fact, you will see throughout the book that Taubes will cite observational studies, usually without caveat, if it fits his meat-is-good narrative. However, if he doesn’t like the conclusion of a study (observational or otherwise) you will find that he impugns the methodology, the authors, or even the entire field of science of which it is a part. Get your popcorn ready.

* * *

Like the above point, this is not a real significant issue, but it shows that Taubes is not above quote mining to try and paint someone in a negative light. On page 16:

Henry Blackburn, his longtime collaborator at Minnesota, described him as “frank to the point of bluntness, and critical to the point of sharpness.” David Kritchevsky, who studied cholesterol metabolism at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia and was a competitor, described Keys as “pretty ruthless” and not a likely winner of any “Mr. Congeniality” awards.

I imagine the point of these quotes is to paint Keys as kind of an asshole, just in case any reader might find themselves sympathizing with Keys when Taubes takes massive, diarrhea-like shits all over Keys’s research and Keys personally. I cannot verify the Kritchevsky quote above because it was from a personal interview, but adding a bit of context to the Blackburn quote can change the tone entirely4:

Ancel Keys has a quick and brilliant mind, a prodigious energy, and great perseverance. He can also be frank to the point of bluntness, and critical to the point of sharpness. But by the boldness of his concepts, the vigor of his pursuits, and the rigor of his methods, as well as by his personal example, he led several generations of investigators in making powerful contributions to the public health.

The entire article is actually quite praiseworthy.

* * *

Pg. 15:

This was a common finding by heart surgeons, too, and explains in part why heart surgeons and cardiologists were comparatively skeptical of the cholesterol hypothesis. In 1964, for instance, the famous Houston heart surgeon Michael DeBakey reported similarly negative findings from the records on seventeen hundred of his own patients. And even if high cholesterol was associated with an increased incidence of heart disease, this begged the question of why so many people, as Gofman had noted in Science, suffer coronary heart disease despite having low cholesterol, and why a tremendous number of people with high cholesterol never get heart disease or die of it.

I’m not sure why Taubes names DeBakey as the primary source here, since he was actually the fourth author in the study that was cited, but no matter… It’s interesting to find that if you check the 1964 paper that is cited, it’s a type of observational study called a case series that examines 1,700 surgical patients treated for some sort of atherosclerosis.5 Turns out 1,416 out of the 1,700 (or 83%) have what the Mayo Clinic would describe as “high” cholesterol levels (over 200 mg/dL).

Does Taubes even read the studies he cites? Or does he read them and deliberately misrepresent them?

A second paper he cites in support of that paragraph is not even a study, but a statement by the president of the American Heart Association6 (wait… they’re supposed to be the bad guys, right?). He says many things in that statement, but what is most relevant to this paragraph is he says that

In a nation of over a quarter of a billion people we are a remarkably heterogeneous lot, and in truth there are no two of us alike. Those with low cholesterols as a group seem to have less coronary disease than those with high cholesterols, but this is too often extrapolated to apply directly to one individual.

He goes on to expound that, sure, cholesterol levels are important, but sometimes people get heart disease and don’t have high cholesterol levels so we should individualize our advice. I don’t think it really helps or hurts Taubes’s argument, but evidently he cited it anyway. Probably to pad his references.

* * *

If Taubes’s irrational contempt for Keys was not obvious before, it should be crystal clear after this passage on page 16:

When Keys launched his crusade against heart disease in the late 1940s, most physicians who believed that heart disease was caused by diet implicated dietary cholesterol as the culprit. We ate too much cholesterol-laden food—meat and eggs, mostly—and that, it was said, elevated our blood cholesterol. Keys was the first to discredit this belief publicly, which had required, in any case, ignoring a certain amount of the evidence.

Before Keys came along all of the “evidence” that dietary cholesterol substantially affects serum cholesterol was from animal studies. Studies that, just two pages earlier, Taubes argues have no bearing on human physiology. So Keys decides to conduct some cholesterol research on actual humans, and concludes that dietary cholesterol actually doesn’t have a substantial effect on serum cholesterol.7 If this were anyone else other than Keys Taubes would likely praise them for not following the conventional wisdom of the day and conducting proper scientific research, but instead Keys is accused of “ignoring” evidence. I think that’s fair.

In the same paragraph as above Taubes discusses a cholesterol study:

In 1937, two Columbia University biochemists, David Rittenberg and Rudolph Schoenheimer, demonstrated that the cholesterol we eat has very little effect on the amount of cholesterol in our blood.

Although the statement “the cholesterol we eat has very little effect on the amount of cholesterol in our blood” is true for most people, as we have just discovered, the Rittenberg/Schoenheimer study that Taubes mentions has almost nothing to do with that statement.8 Firstly, the study was conducted on mice, and extrapolating results on people from cholesterol studies on animals are certainly dubious as Taubes himself admits. Moreover, the study itself involves feeding mice water labeled with deuterium then measuring deuterium in their cholesterol and fatty acids in the mice’s tissues to see how much deuterium had been incorporated into those molecules. As far as I can tell it has nothing to do with feeding them cholesterol and seeing if that impacts their blood cholesterol levels. But correct me if I am wrong.

Pg. 16 continued:

As a result, Keys insisted that dietary cholesterol had little relevance to heart disease. In this case, most researchers agreed.

Most researchers agreed… 16 years later.9

* * *

On page 17 Taubes writes:

By 1952, Keys was arguing that Americans should reduce their fat consumption by a third, though simultaneously acknowledging that his hypothesis was based more on speculation than on data: “Direct evidence on the effect of the diet on human arteriosclerosis is very little,” he wrote, “and likely to remain so for some time.”

This is another minor point, but it should be pointed out that THAT IS WHAT A HYPOTHESIS IS. It’s a guess based on little or no evidence, and all scientists have them. Just for context, here’s the quote from Keys that Taubes plucked with a bit more… umm… context10:

[W]e may remark that direct evidence on the effect of the diet on human atherosclerosis is very little and is likely to remain unsatisfactory for a long time. But such evidence as there is, plus valid inferences from indirect evidence, suggests that a substantial measure of control of the development of atherosclerosis in man may be achieved by control of the intake of calories and of all kinds of fats, with no special attention to the cholesterol intake. This means: (1) avoidance of obesity, with restriction of the body weight to about that considered standard for height at age 25; (2) avoidance of periodic gorging and even temporary large calorie excesses; (3) restriction of all fats to the point where the total extractable fats in the diet are not over about 25 to 30 per cent of the total calories; (4) disregard of cholesterol intake except, possibly, for a restriction to an intake less than 1 Gm. per week.

Taubes gets the quotation a smidge wrong, but it still keeps the spirit of the original. The bigger picture here is that Keys is recommending (in an academic journal, by the way) to avoid becoming obese, avoid gorging on food, a diet that’s about 30% fat, and to not worry too much about cholesterol intake. Pretty uncontroversial stuff, if you ask me. Yet Taubes portrays Keys here and elsewhere as some kind of radical crusader, religious zealot, idiot, and kind of an asshole.

* * *

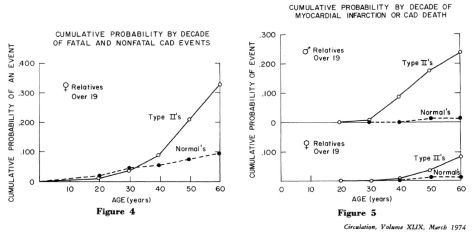

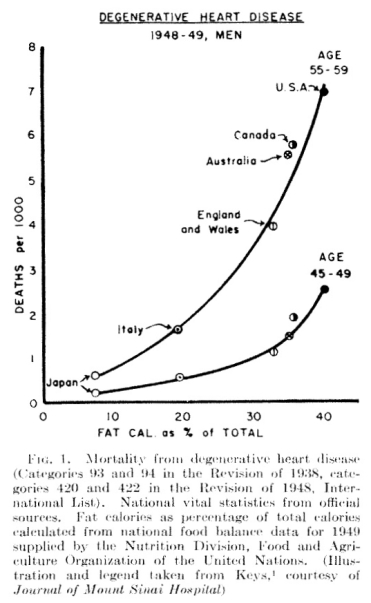

On page 18 Taubes discusses a 1957 paper by Jacob Yerushalmy and Herman Hilleboe, which is something of a response to Ancel Keys’s 1953 paper Atherosclerosis: A Newer Problem in Public Health.11 If you’re not familiar with the Keys paper I will give you a brief synopsis. Keys published some data that suggested a remarkable relationship between fat in the diet and heart disease. Included in the paper was a striking (if oversimplified) figure looking at several countries and their population’s typical fat intake juxtaposed with deaths from heart disease.

Taubes says:

Many researchers wouldn’t buy it. Jacob Yerushalmy, who ran the biostatistics department at the University of California, Berkeley, and Herman Hilleboe, the New York State commissioner of health, co-authored a critique of Keys’s hypothesis, noting that Keys had chosen only six countries for his comparison though data were available for twenty-two countries. When all twenty-two were included in the analysis, the apparent link between fat and heart disease vanished. Keys had noted associations between heart-disease death rates and fat intake, Yerushalmy and Hilleboe pointed out, but they were just that. Associations do not imply cause and effect or represent (as Stephen Jay Gould later put it) any “magic method for the unambiguous identification of cause.”

I have actually written about this in a previous blog post, but I will revisit this again. Aside from the fact that Keys never claimed a cause-and-effect relationship (much less an unambiguous one) and always identified it as an association, Taubes completely misrepresents the results of the study. It’s true that after Yerushalmy and Hilleboe added more data into the graph the relationship becomes a bit more muddied, but it certainly does not vanish as Taubes claims. There is still a noticeable relationship.12 See for yourself.

What’s even more interesting is that Y&H actually conclude that consumption of animal fat and/or animal protein is much more strongly associated with heart disease than total fat. Moreover, vegetable fat and/or vegetable protein is actually negatively correlated with heart disease. The resolution is not very sharp, but here are the results. I’ll leave it to you to wonder why Taubes ignores this highly pertinent information.

* * *

On pages 19-20 Taubes claims that Keys “insisted” that fat elevated cholesterol. I am not sure what Keys was doing that made him so insisting, other than writing a few academic articles concluding that there was an association between dietary fat and serum cholesterol (which there was), while also making sure to point out that there are many details about this association that have yet to be discovered (which there also were). Taubes then goes on to mention some studies that examined those details:

In 1952, however, Laurance Kinsell, director of the Institute for Metabolic Research at the Highland–Alameda County Hospital in Oakland, California, demonstrated that vegetable oil will decrease the amount of cholesterol circulating in our blood, and animal fats will raise it. That same year, J. J. Groen of the Netherlands reported that cholesterol levels were independent of the total amount of fat consumed: cholesterol levels in his experimental subjects were lowest on a vegetarian diet with a high fat content, he noted, and highest on an animal-fat diet that had less total fat. Keys eventually accepted that animal fats tend to raise cholesterol and vegetable fats to lower it, only after he managed to replicate Groen’s finding with his schizophrenic patients in Minnesota.

In other words, Keys did what any good scientist should do: he followed the evidence. Yet the syntax of the last sentence would have you imagine that Keys was some sort of stubborn asshole that refused to accept the truth until the evidence overwhelmed him.

* * *

This may be another nitpicky issue, but the following quote is misleading. Page 20:

This kind of nutritional wisdom is now taught in high school, along with the erroneous idea that all animal fats are “bad” saturated fats, and all “good” unsaturated fats are found in vegetables and maybe fish. As Ahrens suggested in 1957, this accepted wisdom was probably the greatest “handicap to clear thinking” in the understanding of the relationship between diet and heart disease.

First of all, I was never taught that kind of “nutritional wisdom” in high school. Come to think of it I was never taught any nutritional wisdom in high school, but that’s neither here nor there. My issue with this is that in the text that Taubes cites as the source of that quote, Ahrens does not say that the animal fat = bad / vegetable fat = good binarism is the greatest handicap to clear thinking. What he does say is that the good-bad dyad was a greater handicap than the confusion about why experimental diets were designed to be eucaloric.13

* * *

Tabues uses a 1957 review article titled “Atherosclerosis and the Fat Content of the Diet” as a source for three claims in this chapter. One is simply a block quote on page 8. The other two claims are very tenuous, especially the following found on page 20:

In 1957, the American Heart Association opposed Ancel Keys on the diet-heart issue.

The article does mention Keys a few times, as well as a number of other researchers involved with dietary research involving atherosclerosis, but it is very neutral on Keys. In fact, you might even say the author mildly endorses Keys at a couple of points: “Mayer et al. found that high-fat animal or vegetable diets increased and low-fat diets decreased serum cholesterol of normal subjects, confirming earlier data of Keys.” And “Keys, in particular, has placed emphasis on the proportion of total dietary calories contributed by the common food fats […] Certainly there is an abundance of data, both clinical and experimental, that tends to relate excess fat intake to atherosclerosis.”14

After reading the article I certainly didn’t get the idea that the AHA opposed Keys. Even if they did they never explicitly stated this.

* * *

On page 21 Taubes pulls some numbers from thin air:

As Time reported, Keys believed that the ideal heart-healthy diet would increase the percentage of carbohydrates from less than 50 percent of calories to almost 70 percent, and reduce fat consumption from 40 percent to 15 percent.

The Time article actually does report that Keys suggested American reduce their fat intake from 40 to 15 percent. However, there is no mention in the entire article about Keys recommending an increase in carbohydrates.15

Go to Good Calories, Bad Calories: A Critical Review; Chapter 2 – The Inadequacy of Lesser Evidence

Refs

4. Blackburn, H. Ancel Keys. at http://www.mbbnet.umn.edu/firsts/blackburn_h.html

10. Keys, A. Human Atherosclerosis and the Diet. Circulation 5, 115–118 (1952).

This is the 1936 paper you’re probably talking about but I’m unable to find it anywhere

Landé K. E., Sperry W. M. (1936) Human atherosclerosis in relation to the cholesterol content of the blood. Arch. Pathol. 22:301–312

That’s the one. I just can’t find it available online or in my university’s archives.

so where did Taubes get a copy from?

That’s a good question. Likely from the Columbia University’s archives, but I really have no idea.

I found it here with a DOI:10.1001/jama.1936.02770500036012

Sci-hub: 10.1001/jama.1936.02770500036012

That’s close, but not quite it. The paper you cited is an editorial in JAMA that briefly discusses the study, but the text of the original study is in the Archives of Pathology. I still can’t seem to find it, but here’s a link to some info about it: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19361403668

See if you can find a DOI number for it.

Hi, Seth,

Great review. Like you, I found Taubes’s book full of misinformation, cherry-picking, misreferenced studies, incorrect physiology, confirmation bias, etc, etc, etc. I had begun a chapter-by-chapter review myself back in 2010 on my website here:

http://weightology.net/?p=265

I started with the obesity stuff as that is my primary interest. I never did continue on due to life getting in the way, but not too long ago I made another post challenging Taubes’s knowledge of what a hypothesis means and what it means to test it.

http://weightology.net/?p=1081

Keep up the good work.

James

Kewl! Thanks for the kind words.

I’ll check out your stuff. I know what you mean about life getting in the way. It’s time-consuming work and one can lose steam easily.

Can you perhaps pay to download that Lande/Sperry paper via this link?

http://www.ahjonline.com/article/S0002-8703(37)90941-4/abstract

Wishing you enduring health

Ivor Goodbody

“Keys was the first to discredit this belief publicly, which had required, in any case, ignoring a certain amount of the evidence.”

My read of this sentence is that Keys publicly discredited the belief and to hold the belief required ignoring a certain amount of the evidence which Taubes tries to outline in the next sentences. I think he was trying to say that Keys gets more wrong than right and when he gets stuff right it’s obvious and most many didn’t ascribe to the belief. I have no reason to doubt that most did not believe accept that dietary cholesterol caused atherosclerosis at that time. But perhaps Taubes should have given more credit to Keys for coming up with a scientific analysis of the effects in humans.

Maybe you and Krieger could consider combining your efforts and publishing an ebook about Taubes on Amazon Kindle…?